The day begins early in Chester, West Virginia, a town of a few thousand that hugs the southern bank of the Ohio River. It’s only 8:30am but John and Peggy are already bundled up in their coats, hats, and gloves as they take their three bird dogs outside for some crisp January air.

Eventually both man and animal tire of the winter, and they return inside for breakfast. Outside their kitchen window, half a dozen blue jays sit perched in a single tree; John complains that they’ve already eaten the seeds he set out when he woke up. As Peggy prepares drinks and warms up maple syrup, her husband begins laying strips of bacon on the griddle. They’re soon replaced by fresh pancake batter, filled with extra helpings of Georgia pecans (a staple ingredient in their household). Their playful banter from opposite ends of the kitchen is a testament to over forty years of marriage.

After breakfast, John is free to relax in one of the two leather recliners in the living room. There’s no football on TV that Saturday, so his schedule is open, beyond dinner plans with another couple that Peggy reminds him of before she leaves to run errands. He waves goodbye.

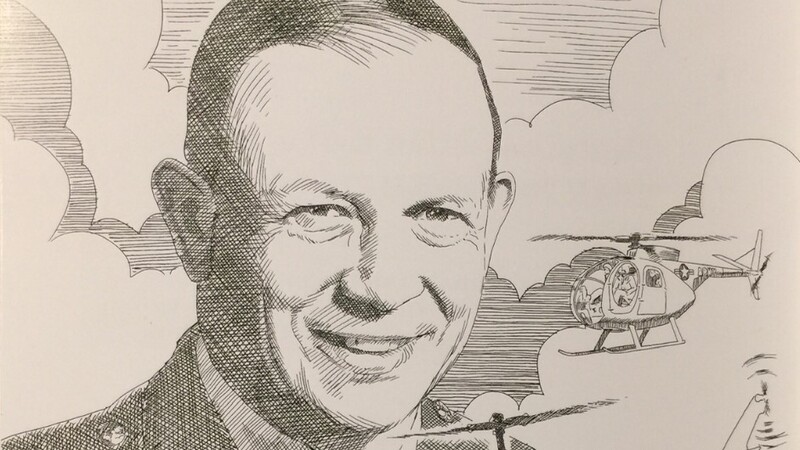

Their first impressions to a stranger may be only as a kind, affectionate couple enjoying an active retirement. But in this welcoming home, nestled in the northern most corner of West Virginia’s panhandle, lives one of the most decorated soldiers in U.S. military history. And he is ready to bring our troops home.

John Bahnsen began life in rural Georgia, and that Southern Pride—so emblematic of the region—remains as embedded in him as the day he was born. He still owns a home in the state, one that rests on four and a half acres of pecan orchard that keeps him well supplied. Growing up among bird dogs, cotton fields, and the strenuous life of an outdoorsmen, John decided early on he wanted to be a soldier. Both he and his brother Peter received appointments to the U.S. Military Academy.

It was at West Point that Bahnsen forged lifelong friendships. First among them was his classmate Norman Schwarzkopf, the future head of U.S. Central Command who led an international coalition to victory in the Gulf War. But before that, in his youth, Schwarzkopf was helping raise a little hell.

“Schwarzkopf came over with three other classmates,” Bahnsen recalls six decades later. “I had them sitting in the back of my Ford Convertible, sitting there with a shotgun, and riding down the dirt roads of south Georgia shooting doves off the powerline.” It was an eminent group of second lieutenants. Four of them—Schwarzkopf, his roommate Leroy Suddath, Bahnsen, and John W. Nicholson—went on to become general officers. “They had dinner over at my place there and my mother and father fixed food for them. But Schwarzkopf, we hunted quail, shot doves off the powerlines, had a great time. I think we went rabbit hunting at night, shooting things off the road. Which is illegal as hell.”

Schwarzkopf—who wrote the foreword to Bahnsen’s 2007 co-authored autobiography, American Warrior: A Combat Memoir of Vietnam—isn’t the only friend who achieved larger than life status. “I’ve known Colin Powell since he was a Captain,” Bahnsen brags about the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs and Secretary of State. Another is ret. Lieutenant General and former National Security Advisor H. R. McMaster (“one of my best friends”).

Beginning his own career in the infantry, Bahnsen attended Airborne School and Fixed Wing Flight School before transferring to the Armor branch while stationed in West Germany. In October 1965 he reported for duty at Bien Hoa Air Base in Vietnam, just south of Saigon. There he commanded the “Bandits,” a gunship platoon for the 118th Aviation Company.

Bahnsen’s second tour in Vietnam—following two unsatisfying years as a staff officer at the Pentagon—was under the command of then-Colonel George SmithPatton, son of the legendary World War II General and another West Point friend. Serving under Patton’s 11th Armored Cavalry “Blackhorse” Regiment, Bahnsen led an assortment of UH-1 and OH-6 helicopters, AH-1 gunships, and an infantry aero rifle platoon into the jungles and skies of Southeast Asia.

“My mission was initially to find the bastards so we could pile-on,” Bahnsen explains. “I was good at it…[Patton] said, ‘You find them, and we’ll pile-on.’ And I found them, and we’d get an engagement, and then by god we’d pile-on with armored troops. But only [after] we pounded them into the ground.”

“It’s the way Americans are supposed to fight a war; with whatever we have that gives us an advantage,” he continues. “Then by golly you save lives. The whole idea of going to war, if you’re a commander, is to save the lives of your soldiers and destroy the other force.”

Fighting from his UH-1 helicopter and leading operations on the ground, Bahnsen and his men saw over three hundred enemy engagements over twelve months. In his final Officer Efficiency Report, Colonel Patton described his subordinate’s innate leadership ability and skill at flushing out the Viet Cong:

“The rated officer is the best, most highly motivated and professionally competent combat leader I have served with in twenty-three years of service, to include the Korean War and two tours in Vietnam…He is one of those rare professionals who truly enjoys fighting, taking risks and sparring with a wily and slippery foe. He is utterly fearless and because of this, demands the same from his unit…I cannot praise Major Bahnsen too highly for his fantastic performance in battle.”

Entering Vietnam as a Captain, he left in September 1969 as a Major, the only one to command a “Blackhorse” squadron during the war. For his bravery, heroism, and quick thinking, Bahnsen was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, five Silver Stars, four Legion of Merits, three Distinguished Flying Cross’, four Bronze Star Medals, two Cross’ of Gallantry, two Purple Hearts, and fifty-one Air Medals, among others. He’s been recognized as a distinguished graduate of West Point, enshrined in both the Army Aviation Hall of Fame Fort Rucker, Alabama, and Georgia Hall of Fame in Warner Robins, invited to participate in the Gathering of Eagles program, and honored by a resolution of the West Virginia legislature. Today, his numerous medals, awards, and recognitions form the centerpiece of his living room coffee table.

After the intensity of the Vietnam War, the remainder of Bahnsen’s career was relatively quiet. With early promotions to Lieutenant Colonel and then Colonel, he served another tour in West Germany, along with South Korea and some time stateside. He retired in 1986 as a U.S. Army Brigadier General.

Bahnsen moved to West Virginia (his wife’s home state) in 1995. Peggy is also a veteran and retired with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel after becoming the first woman to serve as a regimental tactical officer. Their current residence has been in her family since it was constructed in the 1840s.

The couple became politically active in retirement, and both have served on the state’s Republican Committee. It’s not uncommon for prospective candidates to make sojourns to his home for invitation-only dove hunts and request an endorsement. “Everybody loves Reagan,” Bahnsen chuckles, explaining his politics. “I love Barry Goldwater.” The one issue he self-identifies as “a liberal” on is school lunches, which he believes every American child is entitled to free of charge.

The issue that has captured his attention, however, and spurred on the righteous anger of this old warfighter, are his country’s endless wars in the Middle East. He wants to do something about that.

“When Pat came up with this thing about not deploying the National Guard, I said right on. Exactly right. Why the hell are we sending those guys somewhere [when] we have no say for it?” Bahnsen asked.

Pat McGeehan, whom the general refers to affectionately as his “godson,” has represented the people of Hancock County in the West Virginia House of Delegates since 2014. McGeehan, a graduate of the U.S. Air Force Academy who served as an Intelligence Officer in the Middle East, has become a kind of pupil to the elderly general. His signature piece of legislation, “Defend the Guard,” is a bill that would prohibit a state’s National Guard units from being deployed into active combat overseas without a formal declaration of war.

Article I, Section 8, Clause 11 of the U.S. Constitution stipulates that the power to declare war is invested in Congress, the people’s collective representatives, and not a singular executive figure. Despite this clearly defined obligation in its founding document, the U.S. government has not had a formal declaration of war since World War II. Since then American foreign policy has been conducted using either extralegal word games—such as referring to the Korean War as a “police action”—or Authorizations for the Use of Military Force (AUMFs) that, while passed by Congress, are open-ended deferments of action to the Executive Branch. Instead of making the decision themselves, AUMFs are Congress booting the question to the President.

Since the launch of the Global War on Terror in 2001, the National Guard has been instrumental in forming the backbone of military operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere. If enough states were to enact “Defend the Guard” and deprive the federal government of this manpower, it would obligate the cessation of permanent overseas military occupations, nullify the government’s ability to begin new illegal wars, and force a reassessment of the United States’ national interests.

A reassessment is what John Bahnsen is demanding. A longtime critic of America’s twenty-first century foreign policy, he believes the War on Terror—with its trillions in spending, thousands of military dead, and politically destabilizing effects around the world—has severely damaged the national security of the United States.

“How we got mixed up in the Middle East I’ll never understand,” he says, although he has clear suspicions. “We really made a mistake in my mind. The Saudis talked us into coming over…They let the Americans fight that damn war [Gulf War].” Bahnsen recollects with noticeable disgust a Saudi prince and brigadier general in their army (“a flat coward who refused to fight”) who hid in the United States and refused to return to Saudi Arabia until war’s end.

In 2002—2003, while the Pentagon was busy hiring seventy-five retired officers to sell the invasion of Iraq in cable TV interviews, Bahnsen knew better. “We should have never gone to Iraq,” he says adamantly. “We did not have just cause to attack Iraq, we really didn’t…[George] Bush didn’t have anybody declare war on him. Bush declared war on Saddam Hussein, and he got away with it because of weapons of mass destruction. My good friend Colin Powell made the presentation and it was a phony presentation. They didn’t have the facts.”

His opposition at the time was both public and communal, as he laid out the antiwar cause to local Rotary clubs. “I went and flew down to Georgia one time to give a talk down there about the fact that you’re going to regret us going to war because you’re going to have casualties in your hometown, not only wounded…but you’ll have people killed in action in a war we shouldn’t be involved in,” he says.

Bahnsen has particular ire for the men who carried out the post-invasion occupation, Coalition Provisional Authority head Paul Bremer (“a guy who couldn’t speak the language”) and Secretary of Defense Donald “Dumbsfeld” Rumsfeld (a man “with a very small head and a great big ego”).

His assessment is no less critical towards Afghanistan, which at nearly twenty years is the longest war in American history (even longer than his own Vietnam). “We went after Osama bin Laden but once we got him we didn’t decide to pull out,” he says.” “We’ve been there more than long enough. We’ve not got the job done, we’ll never get the job done, it’s not our job to do it. We’re not nation-builders.”

This is one Vietnam veteran who has no illusions about imposing Western, liberal democracy on Afghanistan, or defeating the Taliban and their local Pashtun supporters. “What has the Taliban done to us other than kill Americans because we’re in their country?” he asks. “I don’t like the idea of how they treat women or anything else, I don’t like a lot about them. But that’s their nation and that’s their argument, not ours.”

When discussing America’s endless wars in the Middle East, Bahnsen repeatedly emphasizes the importance of endgame and knowing the conditions of victory. “We didn’t have an endgame plan in Vietnam. We ended up just walking away, leaving our friends there to pay the price (most of them with their lives).”

He sees the same thing happening now. “In Afghanistan we need an end of mission. Nobody can define that. Iraq, end of mission. What is our end of mission? We had an end of mission in Kuwait because once we threw the Iraqis out it was over. Pull the troops out, come home, declare victory, be done with it. We went into Iraq and we’re still there and George Bush put us there.”

“The Powell Doctrine is still good. Go with overwhelming force and declare an endgame,” Bahnsen counsels. “We don’t know what end game means.”

The U.S. Congress, which for over seventy years has refused to debate a declaration of war, shoulders considerable blame for the current mess. They’ve been delinquent in their most important duty, sidelining themselves and refusing to hold the Executive Branch to account for its abuses.

According to Bahnsen, this is a side effect of members being increasingly distant from the military and the risks to life and limb that are inherent in war. “You look at the Congress right now, and just go down the list of congressmen you see there. Tell me how many have skin in the game…That means kinfolks in the game. Damn few. The people who pass laws to send people to combat or the danger of combat or losing their life, they ought to have some kinfolks involved in it. They ought to have some personal involvement, not an abstracted vote.”

“You know my feeling is, before we start committing people’s lives—not yours, theirs—you ought to decimate the Congress. When you have a war you put every tenth man in Congress [and] you designate him to go in a front-line unit. That’s the law you ought to have,” he suggests.

For members of Congress, most of whom haven’t served in uniform and who even fewer have children currently serving, foreign policy has become sterile. It is easy to say, as Rep. Liz Cheney (R-WY) has, that the United States should never leave Afghanistan—as long as you don’t have to witness the human consequences.

“One American life is worth a lot to me, personally. You just can’t wave away a dozen people getting killed a year and that’s the price we pay. Bullshit!” Bahnsen exclaims.

“I maintain that if people haven’t seen their people die, seen people bleed out, have their guts blown out or part of their head blown off in combat, or see them in a wheelchair like I’ve done… You don’t understand,” he explains. “And my feeling is now don’t commit people unless you have a damn reason to do it. And it should be voted on. And the country should go to war with one reason and one reason only: to win the war.”

“I can make a very good case as a decorated soldier, having people killed in combat under my command—volunteers in a war that’s not been declared by this country [but] that somebody decided we should go fight—that is wrong,” Bahnsen says, explicitly calling Vietnam an “illegal war.”

None of the United States’ current enemies constitute a national threat, and none of its wars of choice are to defend the liberty of Americans. “If I thought we were going to lose our basic freedoms of speech, religion to something like that, yeah I’d be willing to go to war then. Then I’d line up my neighbors and my friends and my kids and my family and go pay the price to try to retain it. But not until.”

With the colossal influence held in Washington DC by the military-industrial complex and foreign lobbies, and a Congress content to be missing in action, it is unlikely that constitutional war powers will be restored at the national level (at least in the short term). That is why the responsibility falls upon state legislatures and local representatives to restore sanity to U.S. foreign policy. General Bahnsen believes “Defend the Guard” is the best way to accomplish that.

“You’ve got the power in Charleston [West Virginia] to say, ‘We will not permit our national guard to be federalized unless there’s a declaration of war,’” he says. “They owe it to their citizens and their constituents to take care of them and protect them from things like that. And I would have their ass if they didn’t.”

“My feeling is, do good things for your constituents, whatever that is. And if you don’t, then by god be prepared to explain yourself,” warns Bahnsen.

State legislators who have introduced “Defend the Guard” bills have been browbeaten by their state adjutant generals and officials at the Pentagon who are more interested in system preservation than prioritizing the lives of American soldiers. Backroom threats by the federal government have included withdrawing National Guard units from their states and seizing their military equipment. What is General Bahnsen’s response to this intimidation? “I’d tell them to get fucked,” he says flatly. “I don’t think they have the power to do that.”

By the end of the 2021 legislative session, “Defend the Guard” will be introduced in over thirty states. This is a triumph for the supermajority of veterans—over 66% in multiple polls—who want to see a U.S. withdrawal from places like Iraq and Afghanistan and the start of a more restrained foreign policy.

It is no surprise why veterans, who have seen the horrors of war firsthand, support these polices at even higher rates than the average civilian. “I pass pictures of guys I have hanging up here. I look at one of my books there, I knew those guys. They’re dead! They didn’t get a chance to have a kid or a grandkid. Some of them were too damn young to get married. Good lord. I just think that’s atrocious to have people making that decision,” mourns Bahnsen.

Initially raised as a Baptist and married in an Episcopal Church, Bahnsen has since left organized religion. This is partially because many local churches in the area (including one founded by Peggy’s Presbyterian ancestors) have either folded or amalgamated, and partially because of personal conviction. “I’m not worried about my spirit,” he says. “I lived a good life, I treat people right, I believe in the golden rule, that’s fundamental religion. I don’t need the Bible to tell me that.”

“I appreciate life more the fact I’ve lived as long as I have. My father died at age 59. My mother died at age 65. They didn’t have a complete life in my mind,” he continues, reflecting that over half of his West Point class (including Schwarzkopf) have passed away. “I’m 86. Now 31 years ago I had triple bypass [and] I’m still around…I’ve got a good wife who treats me good, lets me sleep in the chair on a regular basis, feeds me every once in a while. I’ve had a good life.”

Brigadier General John Bahnsen is at peace with himself. Now he only wants to see peace for his country. And “Defend the Guard” is the way he’ll do it.